UNDERSTANDING SPEED IN THE MODERN GAME OF NETBALL

By Ranell Hobson

The game of Netball comprises of explosive short acceleration, vertical propulsion, catching, passing, defending and shooting where a team’s success is largely dependent on their ability to maintain and take possession of the ball and accurately shoot to score points. In the modern game, Netballers accelerate, sprint, decelerate, stop, change direction and reaccelerate at a faster rate and in a more hotly contested environment than their predecessors ever imagined. Whether creating space on the court, contesting a pass or blocking an opponent, sprint acceleration and multidirectional speed are a part of every play.

For all athletes the capacity to sustain repeat sprint accelerations to create space on the court and beat opponents to the ball is a critical aspect of success. Players can ensure that their passing accuracy and catching capabilities exceed skill standards, but if they are unable to escape defenders, then those skills become void. Time spent developing the skill of speed in all its components should be of high priority to any athlete striving to play at Netballs highest level.

Just as countless hours are used examining the technical execution of players passing, catching and on court positioning, the same needs to be given to the skill of speed. Understanding postural integrity in acceleration, direction and magnitude of force in foot-strike and manipulation of stride cycles in congested situations is integral, as is the technical execution of a players deceleration and change of direction mechanics.

Athletes need to understand how to use force (lower limb positioning) to sprint and change direction faster and to eliminate energy leaks. This is turn will delay the onset of fatigue, decrease risk of injury and minimize poor decision making.

Agility is a vastly different component, combining the cognitive aspect of an athletes ability to read the game, make swift decisions, and act appropriately, with their physical competencies in sport speed. It is not uncommon for coaches to witness athletes that consistently display great speed in straight line sprints to then falter on the court looking slow and clumsy due to poor decision-making qualities. An athlete’s agility is highly dependent on their experience in the game, the level of play and their positional experience. Highly skilled players make significantly faster decisions than lesser skilled players. Moving a player from one position to another may impact their agility in that role until enough situational experience allows fast (and correct) decisions to be made.

The automation of correct speed mechanics should be the goal, this allows athletes to maintain a solid foundation of safe and effective movement even in the most challenging situations. For this purpose, there are key elements to speed which need to be understood.

Foot Strike :

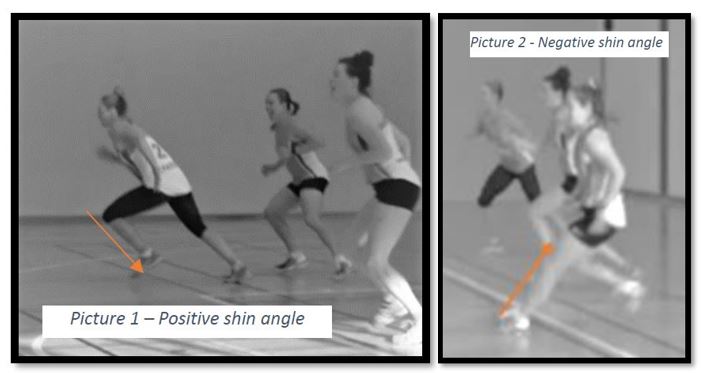

The magnitude and direction of force driving through the foot (known as Impulse) is directly related to how fast an athlete moves, and in what direction that movement takes place. Coaching athletes the importance of shin and foot position for reactionary forces (Newtons third law: Every action has an equal and opposite reaction) is the first step in athletic speed development. Lower limb positions dictate success in acceleration, deceleration and cutting. In acceleration a positive shin angle (Picture 1) will drive an athlete forward, naturally then a negative shin angle (Picture 2) is used to decelerate. Foot strike and lower limb positioning (direction of force) is best coached on the court across a multitude of short acceleration distances.

The magnitude of force applied in acceleration is dependent on the strength and stability of the athlete. During acceleration a foot should never strike the court in front of the knee as this causes deceleration and shearing forces. Coaching athletes to understand skeletal angles within movement gives them the vital information they need for sound mechanics so as to sprint and change direction faster.

Acceleration :

Netballers need the skill to accelerate from both stationary and rolling positions. Explosive acceleration in a multitude of directions from a jog, run or maneuver is most common. When an athlete is driving from outside mid court into the goal third corner, a distance of 15- 18 metres may be traveled. This allows for pure acceleration mechanics to be used, (forward lean, forefoot strike, greater positive shin position). As the body does not accelerate well from an upright position, coaching athletes to drive forward, leaning toward their target in even the shortest of accelerations will get them into space faster.

When players find themselves constrained by opponents in tight spaces and in an upright body position, using toe steering and using an open hip drive allows the player to modify to a shorter stride length and increased cadence. This more effectively negotiates rapid changes in response to stimulus. A great deal of strength and stability is required to execute this competently. When only 2 or 3 accelerating steps take place before a ball skill, the player may adopt a more vertical shin position and a mid-foot strike; this is the art of maneuvering. Although this decreases the effectiveness of lower limb acceleration mechanics, the player is better able to retain a position to stop rapidly and complete game tasks.

Deceleration :

The skill of rapidly decelerating velocity and stopping under control is integral to not only performance but also player safety. Deceleration is a precursor to a change of direction or complete stop and is usually in response to a stimulus. Doing this competently requires a great deal of eccentric strength and dynamic balance. In deceleration, the coach should be looking for the opposite mechanics to those seen in acceleration ie: a rapid shortening of steps where the foot lands in front of the knee with a backward lean, and a lowering of the hips. Athletes in their earliest stages of development should be coached to decelerate and brake in all forward, backward and lateral movement patterns. Athletes must understand how to manipulate their base of support and centre of gravity (wide and low) depending on situational necessities.

Change of Direction :

Sharp changes of direction to break free from opponents is a key characteristic of Netball. Developing competencies in dodging and evading opponents is an important aspect of attacking play. Change of direction in its simplicity is a transition step which moves a player from one direction to the next. Coaching athletes to understand the use of force through the inside and outside edge of the foot as well as toe-steering for directional changes, becomes paramount to provide the athlete with movement tools that breed success.

Loading the inside edge of the foot whilst leaning toward their target increases force into the court. This, paired with an open hip or toe steering maneuver, is best used for congested spaces and small angled transitions. For more aggressive transitions and a more rapid change of direction, athletes should be coached in using an outside edge loading and cross over step transition to evade opponents and create much needed space to receive and catch incoming passes.

Maneuvering (Foot Patterning) :

The specific skill of defensive maneuvering in Netball should be included in all speed programs. Players need to be coached to constantly adjust feet and hips, adapting both centre of mass and base of support, depending on an attacking player or external stimulus. Recovery patterns, footwork movements, blocking and dictating are characterized by small rapid adjustments of position including, Pivoting, Dodging, Reverse and Lateral Shuffling, Sidesteps, Jockeying and Back pedaling. These highly contextual movement skills to track players and counteract an opponents’ movements, are best coached during court work with assessment of movement competencies underlining ball work tasks. In elite performance environments, strength and conditioning coaches should work closely with technical coaches to assess body positioning, posture and mechanics and assign drills to individual players to address observed weaknesses.

Underlying Skills

In all facets of speed there are underlying physical competencies which will dictate the success of training and performance. Postural integrity, Strength, Power, Mobility and Stability of each athlete must be addressed and trained as part of a holistic approach to speed development.

The athleticism of each player must be at least equal to ball skills in time attributed to training. In Netball, possession of the ball is hotly contested and directly impacts the games result. Getting to the ball first, evading opponents, being relentless in defense and being fuel efficient to the final whistle are all markers of an effective speed and change of direction program.

To see FREE training videos of speed and change of direction drills go to www.academyofsportspeed.com and click on the FREE training drills tab for a drop down list.

Ranell Hobson is the Training Director and Head Coach at the Academy of Sport Speed Australia and the Strength and Conditioning Coach for the GWS Fury Premier League Netball Teams. Ranell has consulted to NRL, AFL and A League teams and EPL Academies in the UK. Ranell also coaches National and International Track Athletes in the Sprint events.